Australian sailor and world record holder, Lisa Blair has an inspiring, unbreakable spirit even when she loses her mast and is then crushed by a containership in high seas, a thousand miles offshore.

Her fortitude is astounding and her achievements speak for her. She’s got the fastest time for circumventing Australia on a monohull and is the first woman to sail solo around Antarctica with one-stop and to sail solo around Australia non-stop and unassisted. As part of our More Women at Sea series, Lisa dropped in to share her incredible story and discuss the challenges women face in the industry today.

What hooked you into sailing?

I was working as a waiter in a resort in the Whitsundays and saw the charter boats going on tours of the islands, which looked exciting. I wanted a new challenge and had a few months before university started, so I put a CV in to be a hostess on a sailing boat.

I fell in love with sailing and wanted to become a deckhand but the company wasn’t interested. There wasn’t the conversation around getting women in the industry back then and it was difficult to compete against the men.

After six months of waiting to be a deckhand, I left the company to find more opportunities to get into sailing. After I got my commercial ticket, the original company who refused to hire me as a deckhand took me back as captain! Without that first hostess job, I’d never have got into sailing.

What fueled your idea to sail solo?

My mum’s partner was a sailor and I would read his books about solo heroes, such as Robert Knox-Johnston and Ellen MacArthur. I read about the Clipper Round the World Yacht Race so that inspired me to join the 2011-12 race out of Southampton, UK.

When I joined the Clipper team, I asked a lot of questions as I believe you learn much by watching, reading books and talking to those with experience. I was up the rigging, splicer, watch leader, at the helm and first on the bows. The skipper saw the hunger in me to learn and deliberately gave me challenging situations. I put myself out there so much he gave me his time. There was no segregation between the men and women, which was awesome. I was fortunate to be on the winning boat, Gold Coast Australia.

I had an idea I wanted to go solo but didn’t have enough experience. Clipper fast-tracked my knowledge by 10 years in just 12 months. While sailing with the team, I imagined if I was doing trip alone. How I would cope if this happened? What I would do if this or that broke? At the end of the race, I knew I wanted to give solo a go.

What was it like sailing with Alex Thomson Racing?

After Clipper, I volunteered for Alex Thomson Racing just after he had just achieved the Atlantic speed record. The team offered me a job to fly to Vietnam the next day. Off I went and sailed on his 60ft racing yacht to Singapore and onto Malaysia and Langkawi for three months before they paid for my flight home.

There is nothing like helming that boats on flat seas in Singapore. The skipper spent a lot of time teaching me new systems. It was amazing being close to that level of racing and campaigning, where you can see the immense skills of the people involved and the amount of sponsorship required to keep it going.

In 2014, I completed the Solo Tasman Challenge from New Zealand to Queensland only getting a boat a week before the race.

How did you decide on tackling Antarctica?

Someone suggested Antarctica to me and my first thought was there was not a chance in hell I would tackle the Southern Ocean as it was too dangerous. I kept researching iceberg, storm and temperature data and assessing my abilities. I began to think I could do it and I finally decided to commit to it.

This was back in 2014 and I didn’t get everything together until 2017. The hardest part was funding and I had to keep postponing. In the meantime, I skippered the 2015 Rolex Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race.

To get my boat, my mum tried to refinance her home to help but I got a private loan in the end. Three months before I was due to leave for Antarctica, my boat still needed a refit. I was right on the edge of postponing again when the finance came together and, with the help of 40 volunteers, the boat was ready.

I set sail on 20 Jan 2017 and was exhausted with all the preparations. You focus all your energy on getting to the start line and don’t really think the psychological impact of leaving. On the day I left, I baulked and froze. But as I had spent three and a half years visualizing it, I took some deep breaths and got over it. You really do need to spend time with yourself, working through all the emergencies you might face and how it will feel.

What was the biggest challenge you faced?

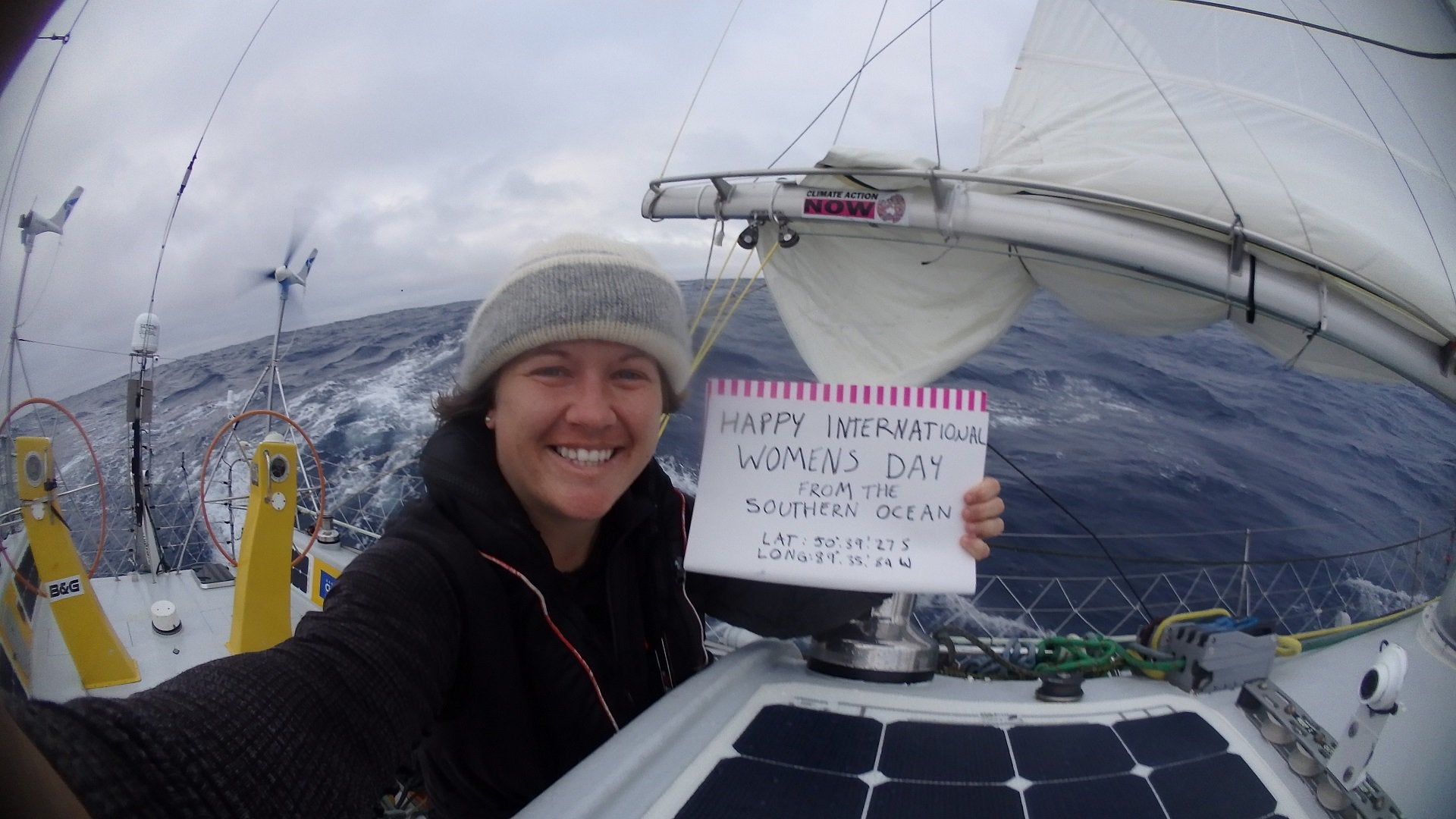

I tracked 40ºS and 60ºS and sailed from Albany, under Tasmania, New Zealand, the South Pacific and around Cape Horn. I hit a huge storm with steep seas up to 10m breaking waves in just 30m water depth and it was freezing. I continued up to the Falklands and South Georgia, heading north to dodge icebergs. The stretch to the Cape of Good Hope was brutal with an average day recording 50-knot winds and 6-8m waves. As I started to head into the Indian Ocean below Madagascar, I lost my mast 72 days into the voyage and 1,000nm from shore.

It was evening, dark and I was below deck when I heard the lower diagonal rigging wire snap. I jumped up and looked at the front of the boat and the mast was like someone doing the hula and shaking their hips. As I went to get my life jacket on, the mast came crashing down with a horrible noise of grinding metal while the boat shook violently. The mast had snapped clean off at deck level and had smashed into the starboard side, destroying the safety rail. It was an extreme case of electrolysis.

A storm was coming in with 30-knot winds and 6m of swell. The boat turned into an anchor, flipping me 180º with the waves crashing over the broken mast. The waves created a push, pull motion and the only way I could free the mast was to go over the broken safety rail. It took me four hours to clear the mast from the boat, which had carved a hole in the deck on the starboard side.

How did you save your boat?

During the mast removal, I faced my mortality and knew there was a 50% chance of getting back on board alive. I was hyperthermic and went below deck to wait for sunrise. When daylight came, I patched the holes in the boat, cut the rigging free, saved the boom and motored to Cape Town.

I got in contact with maritime rescue as I didn’t have enough fuel to get to shore. I requested a fuel transfer and waited three days for a passing containership. My idea was to get fuel into containers and floated out to me but this concept was lost in translation due to a non-English speaking crew. They wanted me to take a 40-gallon drum for my 70-litre tank or a huge line that would have flooded my boat.

I ended up being asked to get close to the ship while it rolled 10m side to side, trying to pass containers on a line. Unfortunately, the ship drifted and crushed the port side of my boat, leaving a 3m crack on the port side and no rails. I was under pressure to abandon but I refused and got my fuel eventually. I built a jury rig, stepped my boom into the old mast, which took two days of angle grinding and working out how to lift it. I modified the storm sails and motored the rest of the way to Cape Town.

What was the turning point?

I had been on my own for over 80 days and was gutted the trip was over as I had put everything on the line. I had the intention to beat the men’s record and I was one day ahead when I demasted. Then I realised I could reset the record by including one stop and got back my energy and positivity. I got a partial insurance payout and sponsorship to get a secondhand mast and rebuilt the boat within two months.

To continue, I needed to sail the Southern Ocean in winter, crossing where I demasted and back to Australia. I researched the weather data and felt that the boat could withstand the storms. But in the first week when I left, I got a head cold and felt really seasick. I was hitting a storm every day and bashing into massive seas, up to 15m, and strong winds that knocked me upside down and then righted me. After a week of doing donuts, I was still only 200 miles from Cape Town. I’d gone nowhere.

I was on the verge of quitting and had spent the week crying, not wanting to quit but knowing I wasn’t well and facing so many doubts. On the same side I knew that if a woman was doing a challenge and failed, she doesn’t get a second chance. My mum put it in perspective. She told me that if my safety was at risk then to return, but if I hadn’t demasted and was at this point, four weeks from the finish line, would I quit? I pressed on, got out of the wind, which made it more comfortable even if I had my first blizzard at sea. I made it although not without stops. I am now looking to re-do this race next year.

What did Antarctica teach you?

Getting the solo record with one stop did give me more credibility with the industry and sponsors and showed how determined I was. You have to prove yourself constantly to people who are full of opinions on whether you can complete the race.

One night I was sleeping on my boat in the marina and heard two men talking. They couldn’t believe I was going solo because I was a woman and even though they knew I had skippered Hobart, they still said my boat was too big.

Women bring a lot to sailing. We tackle stuff differently. When asked about a race, rather than give times or weather report, we will talk about what we feel, missing family and share emotions on a 121 level.

How did the all-female team come about?

I got back from Antarctica and over the next few months developed my next project. I had partnered with The Magenta Project and lead the first all-female team in 16 years to do the race on-board my yacht Climate Action Now.

I partnered with The Magenta Project and we developed it as a mentor program where half the crew were experienced and half were not. It gives them a chance to get bluewater sailing under their belt and to get onto mixed racing teams.

What problems do women sailors face today?

There is still such a stigma about being a woman on the water. It’s important to highlight the conversation around equality and let women make mistakes and learn. It feels very much that if you crash the boat once then you are just a female driver.

When I skippered the 2017 Rolex Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race with an all-women team, I asked applicants if they had faced gender imbalance. Around 90% said they felt they had to work twice as hard to get the same level of recognition as men on a race boat and get to the next level. The women countered this imbalance by being more enthusiastic, putting on a smile and working through it.

How does well-meaning help become an issue?

Sometimes good intentions do not help. You can see this clearly in a typical marina. When a woman parks her boat, dock staff will try to take charge and shout instructions. They might mean to help, but this can be a hindrance. When a guy parks their boat, they just ask where he wants the rope. There is still such different treatment.

I was recently on a Marine Industries Association’s panel on growing female participation in boating. It was great to hear of the many initiatives happening in yacht clubs but they need to be more substantial. For example, many hold a ladies race day, but they do not count to the overall race score. If it did, then there would be more incentives for captains to train women. So, let’s get more training for women and group sailing days.

What’s next for you?

Last December I was the first woman to sail solo around Australia and I am hoping to head back to Antarctica in January without any stops. I’ve even got plans to sail from London around the Arctic. My pressing deadline is finishing my book, Demasted, about sailing around Antarctica, which is being published by Australia Geographic this year. You can preorder the book from my website.

Find out more about Lisa Blair. Come and find more inspiration about sailing over on our blog. For more information on long-term charters or other sailing vacations, get in touch with our team on 1-866-469-0912 or email infona@DreamYachtCharter.com.